^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ Robert Patrick (September 27, 1937) by: Wendell Stone Ohio State University

Influential in both the Off-Off Broadway and the gay theatre movements, Robert Patrick is one of the United States’ most prolific and versatile playwrights, with about 75 published scripts and well over 100 produced plays (over 130 by 1975).

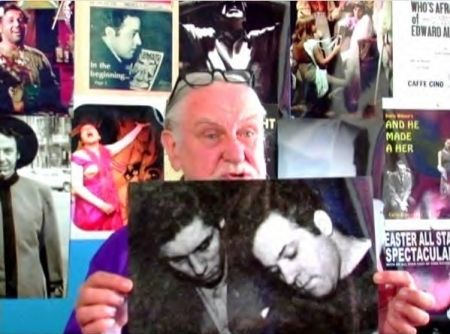

He began his theatrical career at the legendary Caffe Cino, the tiny coffeehouse in New York’s Greenwich Village which was the first and among the most influential and important of the early Off-Off Broadway theatres. His style ranges broadly, from traditional and realistic to highly experimental; like many in the Off-Off Broadway theatre of the 1960s, he began writing in the one-act form, though he is now best known for his full-length play, Kennedy’s Children (1975). In addition to plays, he has written a novel (Temple Slave, 1994) based upon his experiences at the Caffe Cino and several significant critical pieces, most concerned with the creation and reception of gay theatre. He has also contributed poetry to Calliope, Things, Playbill, and FirstHand Magazine and articles to The Drama Review, Saturday Review, Cineaste, Sybil Leek’s Astrology Journal, and Astrology Today. He had regular columns in many periodicals, including Other Stages, The New York Native, Gaysweek, and The Harvard Gay & Lesbian Review.

His recognitions and awards include the Show Business Award for the 1968-69 season (for Fog, Joyce Dynel, and Salvation Army); nomination for a special Village Voice Obie award in 1973; first prize in 1973 for Kennedy’s Children in Glasgow, Scotland from the Citizens’ Theatre’s International play contest; Rockefeller Foundation playwright-in-residence grant in 1973; Creative Artists Public Service grant in 1976; International Thespians Society’s Founder Award in 1980 for services to theatre and youth; Janus Award in 1983; Blue-is-for-Boys Weekends proclaimed by Manhattan Borough Presidents (1983 and 1986); the Bill Whitehead Award for Lifetime Achievement in Gay and Lesbian Literature in 1996; and the Rainbow Key Award from the City of West Hollywood, for “an important voice in American theatre whose numerous works have given voice to the gay experience” in 2008. He is the only person to be given two “Coffeehouse Chronicle” events at La Mama ETC.

Born Robert Patrick O’Connor in Kilgore, Texas, to Robert Henderson and Beulah Adele Jo (Goodson O’Connor Durkee Hawkins Bobo Henson) O’Connor, Patrick grew up in near-poverty in the Dust Bowl as his father moved the family from town to town pursuing employment in the oil fields. Like many of his generation, Patrick was influenced by the radio programs, movies, and other popular culture of the period (references to which often appear in his plays). One of his favorite childhood pastimes was reenacting movies or creating his own plays with his friends and two older sisters. Since he had no knowledge of live performance, his understanding of theatre came from movies, so that he had no concept of the aesthetic differences between the stage and film. His awakening to the power of the stage came during World War II when a traveling theatre troupe was stranded in Grand Prairie, Texas, where he was then living. To finance their continued travels, the troupe hastily raised a tent and offered a variety of entertainments, including a play from the Jewish theatre (though adapted for protestant Christian audiences), a puppet show, and an amateur contest. Patrick’s first performance was his competition in the troupe’s amateur contest. His first performance in a production of a play (as “Simon Stimson” in “Our Town”) occurred in 1955 in Roswell, New Mexico, where, for one of the few times in his life, he attended a full year at one school. As he developed as an artist, Patrick became increasingly convinced of the political, social, and aesthetic power of the stage as compared to film, since the former is an experience shared between the actors and audience at the moment of creation: “Unlike films and literature, which record experiences that once happened, a play presents an event. Its reality makes it a powerful moral and psychological tool. Theatrical artists who do not communicate consciously communicate helplessly and unconsciously.” After attending three years at Eastern New Mexico University in Portales, New Mexico, Patrick worked in the kitchen of a summer stock theatre. At the end of the summer, he traveled to New York City, intending a short visit. During his first hour in the city, he went sightseeing in the city’s bohemian section (Greenwich Village), wandered into the Caffe Cino, and was so intrigued that he became a regular customer. He began volunteering for various chores and soon became an integral member of the Cino crowd, working primarily as doorman but in other capacities as needed (including waiter and actor). He remained in New York for thirteen years, until Off-Off Broadway became, in his opinion, “nothing but showcases for big producers.” With the possible exception of his interest in popular culture, no factor influenced Patrick’s work as much as his experience at the Cino, a venue which presented plays in such divergent styles and on such varied themes that no “Cino style” can be said to have emerged. Patrick describes the importance of the Cino and the Off-Off Broadway movement it nourished as follows: “For the first time a theatre movement began, of any scope or duration, in which theatre was considered the equal of the other arts in creativity and responsibility; never before had theatre existed free of academic, commercial, critical, religious, military, and political restraints. For the first time, a playwright wrote from himself, not attempting to tease money, reputation, or licenses from an outside authority.” Throughout his career, Patrick has remained devoted to the type of theatre epitomized by the Cino: free from constraints, low-budget, and critical of both theatrical and political traditions. Like Caffe Cino itself, Patrick has never settled upon a particular style. As Leah D. Frank has argued, Patrick’s “style has been unique only in its absence, a fact which often drives his critics to despair. It could only be described, perhaps, as Cinoese, or off-off-Broadway eclectic.” Though he was associated with the Cino from 1961, Patrick did not write his first play until 1964 when he presented The Haunted Host to Joseph Cino, the proprietor of the Caffe. Initially Cino tried to dissuade Patrick from becoming a playwright, encouraging him, instead, to continue as stage manager and doorman. Cino allowed Patrick to present his play only after Lanford Wilson (whose first works were also presented at Caffe Cino), Tom Eyen, and David Starkweather intervened on Patrick’s behalf. When the play opened, it was one of a series of works about gay men presented at the Caffe by Patrick, William Hoffman, Lanford Wilson, Doric Wilson, Bob Heide, Haal Borske, Claris Nelson, Soren Agenoux,and other young playwrights*. A two-character piece, The Haunted Host shows the personal growth of Jay, a writer who has sacrificed his career to support that of his less-talented and now dead lover (Ed, the ghost referenced in the title of the play). When beginning-writer Frank enters, he resembles the dead lover both in appearance and behavior; like Ed, he wants to draw emotional and creative support from Jay, a situation which would again require Jay to sacrifice his own talent to nurture that of someone else. Though heterosexual, Frank seems ready to enter into an emotional and, perhaps, physical relationship to attain Jay’s support. In an act of self-protection, however, Jay rejects the opportunistic advances of the younger artist. Patrick has spoken of at least two levels of meaning in The Haunted Host, one general to the gay male community and the other specific to Caffe Cino. By rejecting the parasitic relationship with Frank, Jay has overcome a harmful, demeaning relationship: that between a “heterosexual” male (often a prostitute) and a gay man. By rebuffing Frank’s advances, Jay has, in essence, kicked the hustler out. Patrick has also noted parallels between the relationships of Jay and Frank and those of Joseph Cino and the artists of his coffeehouse. In Patrick’s opinion, Joseph Cino often neglected his own self-interest to provide financial, emotional, and aesthetic support to the actors, directors, and playwrights who worked at his Caffe. Because of the subject matter of The Haunted Host, Patrick had difficulty recruiting actors for the first production so that he had to play Jay. He vividly recalls a particular night when a young man attended the show with his parents; during the production, Patrick overheard the man say, “You see, Mom, Dad? That’s what I am. I’m a homosexual.” That a young man could use his production as a means of coming out to his parents epitomizes for Patrick the importance of the stage as an educational tool and a means of building a gay community. The many productions of The Haunted Host over the years (both in the United States and abroad, some as recently as 1999) show that the play remains stage-worthy and continues to speak to audiences. In addition to its significant position in the canon of gay drama, it is significant in having helped launch the career of Harvey Fierstein who has often appeared in productions of the play (including important tours throughout Europe). Fierstein’s last appearance in the play was in 1991. After the success of The Haunted Host, Patrick continued presenting work at the Cino, with Halloween Hermit and Indecent Exposure in 1966, The Warhol Machine in 1967, and Cornered in 1968. Among the more interesting of the Cino plays is the tri-part Lights/Camera/ Action which was staged in either 1966 or 1967 (sources date the work differently). Each of the three plays deals with the difficulties inherent in communicating in a technological, mediated age. In the first play, Lights, a woman in her forties is assisting a young artist with his show. With her opening lines, she foregrounds difficulties in communication: “No, you don’t understand. How could you understand? For me it’s all over [. . .]. Do you understand? Can you understand?” As the play progresses, she maintains her role as the-one-who-understands as she interprets his artwork for him. Ironically, in presenting her interpretation, she refuses to allow him to speak, taking away his power of communication and reassigning meaning to his work. Thus, the play alludes to the privileging of the older person’s voice over that of the younger and the critic’s voice over that of the artist. Set in the future when interplanetary communication is conducted through televised audiovisual systems, Camera Obscura tells of the first correspondence between a young man and a young woman through such a system. They have difficulty communicating because the distance between them causes a five second delay in the reception of the transmission. Thus, when either of the two attempts to talk, s/he does so just as the signal is being received from the other person, so that the characters’ lines constantly overlap and are repeatedly confused. Since they are allotted only five minutes for the communication, they waste all of their time in confusion and mis-communication. The technological systems intended to foster communication are thus implicated in the breakdown of communication. The third play, Action, is a four character piece which opens on two men (“Man” and “Boy”) onstage, each of whom is composing a script that details the existence of the other. The well-dressed, older Man writes about a young Greenwich Village writer in his underwear working at a typewriter, while the younger Boy (wearing only underwear) types a script about an older, wealthy Man dressed in an expensive smoking jacket and writing into an elegant leather portfolio. Thus the play raises fundamental questions about the nature of reality. Which of the men is “real” and which “fictional”? Is the younger man a product of the older man’s imagination? Or is it the reverse? Ultimately, the dilemma is irreconcilable, since, in a postmodern paradox, the two are co-creative, and are each products of the other’s imagination. Perhaps, also, the play suggests that no work of art exists independently since the creation and reception of art is influenced by other art. Other plays from the 1960s and early 1970s include Still-Love (1968) which traces the love-affair between Gary and Barbara in a series of 21 brief scenes. It does so, however, backwards, beginning with a scene after the end of the relationship and ending with an event prior to the start of the relationship. Cornered (1968) is a two-character play in which a husband returns home to find that his wife has inadvertently painted herself into a corner while painting the floor. Combining two of Patrick’s interests (theatre and astrology), The Golden Circle (1972) is “based on the Rosicrucian-astrological doctrine of the Great Epochs and the recession of the sun” (Biography published with Golden Circle 171). In The Arnold Bliss Show (1972) and Mercy Drop (1973), Patrick explores issues concerning the artist and his/her place in society, including that of sacrificing principle to achieve success. On November 3, 1975, Kennedy’s Children opened at the John Golden Theatre after a brief run Off-Off Broadway and a much more successful run in London (first at a fringe theatre then in the West End, the equivalent of Broadway). Set in a sleazy bar in New York’s lower East Side in February, 1974, the play is composed of a series of monologues delivered by five characters, each of whom relates events that happened in the 1960s: Sparger speaks of his experiences in Off-Off Broadway theatre in a cafe much like Caffe Cino; Wanda remembers President John Kennedy and the effect his assassination had on her; Mark, a drug-addicted veteran, attempts to reconcile his experiences during the Viet Nam war; Carla, a go-go dancer speaks of her failed dream of attaining fame in legitimate acting roles; Rona explores her commitment to various revolutionary ideals of the sixties. Despite the title and the opening sequence (a radio broadcast about a presidential motorcade), the play is less about Kennedy or the sixties than about the loss of heroes, ideals, illusions, and dreams. Unlike many American dramatists, however, Patrick does not simply reveal the illusions underpinning American life. As Scott Giantvalley suggests, Patrick carries his characters beyond the recognition of illusion into the recognition of the need for illusion: “This is not a tragic understanding [. . .] but rather a tranquil acceptance of the fact that illusion is not merely a crutch for the mentally unbalanced but is present to a degree in every human being’s existence. This is one of the central truths of Kennedy’s Children [. . .].” In 1988, Patrick published Untold Decades: Seven Comedies of Gay Romance, a collection of plays about each decade from the 1920s to the 1980s. Fog, the play about the 1960s, was originally produced in 1969 and raises two major issues that appear frequently in Patrick’s work: the struggle between illusion and reality and the destructive emphasis on youth and beauty by many gay men. Set in the Rambles section of New York’s Central Park (which for many years has been a site for sexual encounters between men), the play chronicles a meeting between Fag, a middle-aged, stereotypical gay man and Stud, a young, handsome man. On a night in which a thick fog blankets the dark park, Fag follows Stud into the park, both having just attended the same party. The fog so completely obscures vision that each man can describe himself however he wishes without fear of discovery. Fag and Stud have sharply different concepts what is desirable: Fag: Well, that’s life. Everyone wants the beauties. Stud: I don’t! . . . I mean, I don’t care. It’s not what I’m after. Fag desires youth and physical beauty; Stud is attracted to a man’s intellect and personality and wants others to be attracted to the same in him. Ironically, then, Stud pretends to be unattractive, though Fag ultimately recognizes him as the handsome young man from the party. Fag, on the other hand, pretends to be a “big, blond, beautifully built sex god,” interested in Stud only because of the younger man’s sensitivity and creativity. As the curtain falls, Stud and Fag move toward an even more secluded part of the park to have anonymous sex as the younger man exclaims, “Oh, God! This is the rational world at last,” believing that he has encountered a man who is both handsome and caring. An acclaimed window dresser, Fag has learned to manipulate images to get what he wants and to create an illusion serving his purposes. Currently residing in Los Angeles, Patrick ghostwrites for television, having become disillusioned with actors “who have grown steadily more illiterate in the last thirty years” and with theatre audiences who have “sunk so low that it is no longer interesting trying to entertain them.” His last New York production of a new play was Hello, Bob (1996), composed of twenty-three monologues. Though all monologues are addressed to Robert Patrick (a character who never appears), the focus of the play is hardly on the playwright, but, rather, on the characters who speak and the worlds they inhabit. They include a wide-variety of types, from a beggar on the streets of Manhattan to a director of Bob’s play to a male prostitute. Much more diverse in tone and atmosphere than Kennedy’s Children, it does at moments reach for the poignancy of the earlier work, as, for example, when a high school speech and drama teacher tells Bob that she has decided to quit teaching because of the censorship of texts and response to color-blind casting by the administration of her school: “I couldn’t ever again cast colored people in roles written white. Just as maids and pickaninnies in the nineteen-forties plays they’ve left on the shelves!” As with much of Patrick’s work, he weaves in autobiographical detail, including an incident in which Tennessee Williams (“Tennessee” in Hello, Bob) purposefully irritated a reporter by evading his question to promote one of Patrick’s plays during a live broadcast (the production had not received the attention Williams thought it deserved). Four other one-acts (Ruminations, Evan on Earth, Harbor, and Raise the Children) were produced in New York in the 1990s but were ignored by critics. Two others (Interruptions and Sugar Cookies) were produced in, respectively, a college and a high school in tiny Merced, California, where Patrick lived “in exile” with a sister before finding ghostwriting work in Hollywood. Patrick’s only novel, Temple Slave, appeared in 1994. A fictionalized account of the Caffe Cino, it is the story of a small coffeehouse (Espresso Buono) in the 1960s in New York’s Greenwich Village and of the group of theatre artists who congregated there. It is part homage to the man (Joseph Cino) who made it all possible and part lament for what came of the dreams, work, and hopes of the pioneers of Off-Off Broadway. Though fictionalized, the novel presents a cast of characters recognizably similar to Lanford Wilson, Sam Shepard, H. M. Koutoukas, Tom Eyen, Andy Warhol, Marshall Mason, and others who regularly worked at or frequented Caffe Cino. Reviewer Edward Rubin refers to Temple Slave as the “half-brother” to Larry Kramer’s Faggots because “Both mourn the fading of ideals, the loss of innocence.” Quentin Crisp said of the novel, “Impossible not to mourn this man; impossible not to read this book.” Patrick’s latest work, Film Moi, an autobiography in the form of criticisms of his fourteen favorite films is scheduled for electronic publication in 2000. Patrick’s major non-fiction work consists of several significant essays contributed to scholarly and popular periodicals on the history of Caffe Cino and the development of gay theatre. His “Caffe Cino: Memories by Those Who Worked There” in Los Angeles Theatre Magazine is a valuable compilation of anecdotes of the actors, directors, and writers who presented shows at Caffe Cino, ranging from the famous (Lanford Wilson and Sam Shepard) to the unknown. In essays such as “Gay Theater’s Relationship With Its Audience,” Patrick has examined the history of gay theatre and explored the potential of theatre to help build a gay community. “Gay Analysis,” is particularly interesting as an early example of the use of audience-response techniques in the study of gay theatre. The diversity in style and subject matter of Patrick’s work makes it difficult to extract general characteristics, though he has suggested that his plays “fall into three general classes: 1) simple histories, like I Came to New York to Write; 2) surrealistic metaphors, like The Arnold Bliss Show, Lights, Camera, Action, and Joyce Dynel; and 3) romances, like Fog, Female Flower (unproduced), and both The Golden Animal and The Golden Circle.” Often, but not always, he experimented with form (Kennedy’s Children and Still-Love) or content (The Haunted Host and Mercy Drop). Though a few plays such as Judas (Patrick’s favorite among his works) are quite serious throughout, the vast majority of his pieces are comedies or contain significant comedic components. He is particularly noted for his word play; as Patrick explains, “I’d fling up a palace of puns with an arcade of insults leading to a gazebo of epigrams, letting one line suggest others like a single flake of snow triggering a lacy web of frost on the windowpane.” Critics who have attempted to isolate particular themes in his work include Leah D. Frank who finds “themes of love, greed, pride, and tormented self-doubt” and Gautam Dasgupta who argues that Patrick’s “plays project, at best, a chic, urbane landscape in which the necessity of creating a joyous milieu is highly stressed.” Among additional themes which frequently appear in Patrick’s work are 1) the effort to establish and maintain genuine relationships in face of the oppressiveness of sexism and heterosexism, 2) the struggle to adapt to a changing world, particularly as technology alters the way we communicate and relate to each other, and 3) the struggle between idealism and cynicism. Among the best descriptions of Patrick’s work is that given by Lanford Wilson: “Aside from the funny lines, aside from the rapid pacing, aside from the beautifully balanced construction, perception, the social criticism, Bob Patrick is one of the few writers unafraid of feeling, even when it dips over into sentiment.” Perhaps, however, the best description of Patrick’s work is his own: “My plays are dances with words. The words are music for actors to dance to. They also serve many other purposes but primarily they give the actors images and rhythms to create visual expressions of the play’s essential relationships.” In recent years, Patrick has created an online ARCHIVE of photos from and relating to the Caffe Cino, as well as several Caffe Cino photo albums on Facebook. An April, 2009 Village Voice interview is a curt summary of his philosophy and his lasting reverence for the Caffe Cino.

REFERENCES: Michael Feingold, “Can a Kid from the Caffe Cino Be Really Big, Baby?” The Village Voice (November 17,1975); Michael Feingold, “On Directing Patrick,” in Robert Patrick’s My Cup Ranneth Over (New York: Dramatists Play Service, Inc., 1979) 5-6; William Hoffman, “Foreword,” in Robert Patrick’s Untold Decades (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1988), ix-xi; William Hoffman, “Introduction,” in his Gay Plays: The First Collection (New York: Avon Books, 1979), vii-xxxiv; T. E. Kalem, “Scars of the ’60s: Kennedy’s Children,” Time (November 17, 1975); Jack Kroll, “Howl for the 60s,” Newsweek (November 17, 1975), 93; Larry Myers, “The Caffe Cino Lives,” Greenwich Village Press (April 1995); Edward Rubin, “Book Review: Temple Slave,”Greenwich Village Press (April 1995), 11; Lanford Wilson, “Introduction,” in Robert Patrick’s Cheep Theatricks (New York: Samuel French, Inc., 1972), 1-4.

BOOKS: The Golden Circle: A Fantastic Farce (New York: Samuel French, 1970); Cheep Theatricks! (New York: Winter House, [1972]); Kennedy’s Children (New York: Samuel French, 1975; London: Samuel French, 1975); Play-by-Play: A Spectacle of Ourselves (New York: Samuel French, 1975); One Man, One Woman: Six One Act Plays (New York: Samuel French, 1978); Mercy Drop and Other Plays (New York: Calamus, 1979); Mutual Benefit Life (New York, N.Y.: Dramatists Play Service, 1979); My Cup Ranneth Over (New York, N.Y.: Dramatists Play Service, 1979); Untold Decades: Seven Comedies of Gay Romance (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1988); Bread Alone (Dallas, TX: Dialogus, 1993); Michelangelo’s Models (Dallas, TX: Dialogus, 1993); The Trial of Socrates (Dallas, TX: Dialogus, 1993); Temple Slave (New York: Masquerade Books, 1994). Film Moi: Narcissus in the Dark (Los Angeles: Pagan Press, 2003).

PLAY PRODUCTIONS: The Haunted Host, New York, Caffe Cino, 29 November, 1964; Mirage, New York, La Mama E.T.C., 8 July 1965; Bang, New York, La Mama E.T.C., 3 Nov 1965; Sleeping Bag, New York, Playwrights Workshop, June 1966; Indecent Exposure, New York, Caffe Cino, 27 September 1966; Halloween Hermit, New York, Caffe Cino, 31 October 1966; Cheesecake, New York, Caffe Cino, 1966; Lights, Camera, Action, New York, Caffe Cino, 8 June 1967; The Warhol Machine, New York, Playbox Studio, 18 July 1967; Cornered, New York, Gallery Theatre, 26 January 1968; Un Bel Di, New York, Gallery Theatre, 26 January 1968; Help, I Am: A Monologue, New York, Gallery Theatre, 2 February 1968; Still-Love, New York, Playbox Studio, 18 July 1968; See Other Side, New York, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, 1 April 1968; Absolute Power Over Movie Stars, New York, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, 13 May 1968; Preggin and Liss, New York, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, 17 June 1968; The Overseers, New York, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, 1 July 1968; Angels in Agony, New York, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, 1 July 1968; Salvation Army, New York, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, 23 September 1968; Silver Skies (Music by Walter Harris), New York, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, 1969; Tarquin Truthbeauty, New York, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, 1969; The Actor and the Invader, New York, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, 1969; Presenting Arnold Bliss, New York, New York Theatre Ensemble, 1 April 1969; Dynel (Music by Walter Harris), New York, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, 20 January 1969; revised as Joyce Dynel, New York, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, 7 April 1969; Fog, New York, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, February 1969; I Came to New York to Write (full length), New York, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, 24 March 1969; The Young of Aquarius (music by Walter Harris), New York, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, 28 April 1969; Oooooooops!, New York, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, 12 May 1969; Lily of the Valley of the Dolls, New York, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, 30 June 1969; One Person: A Monologue, New York, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, 29 August 1969; The Golden Animal, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, New York, 1970; A Bad Place to Get Your Head, New York, St. Peters Church, 14 July 1970; Bead-Tangle, New York, St. Peters Church, 14 July 1970; Angel, Honey, Baby, Darling, Dear, New York, Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, 20 July 1970; Picture Wire, New York, St. Peters Church, 13 August 1970; I Am Trying to Tell You Something, New York, The Open Space, August 1970; Shelter, New York, Playbox Studio, November 1970; The Richest Girl in the World Finds Happiness (Music by Rob Feldstein), New York, La Mama E.T.C., 24 December 1970; Hymen and Carbuncle, New York, Dove Company, 1970; La Repetition, New York, Dove Company at St. Peters Church, July 1970; A Christmas Carol (Music by Preston Wood), New York, La Mama E.T.C., 22 December 1971; Valentine Rainbow, New York, La Mama E.T.C., 25 January 1972; Youth Rebellion, New York, Sammy’s Bowery Follies, February 1972; The Golden Circle (Music by Preston Wood), New York, Spring Street Company, 28 September 1972; Play by Play, New York, La Mama E.T.C., 20 December 1972; Something Else, New York, New York Theatre Ensemble, January 1973; Mercy Drop (Music by Richard Weinstock) , New York, WPA Theatre, March 1973 (Music for 1980 revival by Rob Feldstein); Simultaneous Transmissions, New York, Kranny’s Nook, 1 March 1973; The Track of the Greater Narwhal, Boston, MA, Boston Conservatory, 28 April 1973; Kennedy’s Children, New York, Clark Center, 30 May 1973 (West End: London, England, Arts Theatre Club, May 1975; Broadway: New York, Golden Theatre, 3 November 1975); Cleaning House, New York, WPA Theatre, 27 June 1973; Hippy as a Lark, New York, Stagelights II, June 1973; Imp-Prisonment, 1973; The Twisted Root, New York, La Mama E.T.C. 1973; Love Lace, New York, WPA Theatre, 1974; Ludwig and Wagner, New York, La Mama E.T.C., February 1974; How I Came to be Here Tonight, Hollywood, CA, La Mama Hollywood, 21 March 1974; Orpheus and Amerika (Music by Rob Feldstein), Los Angeles, CA, Odyssey Theatre, April 1974; Fred and Harold, and One Person, London, England, 1976; Report To the Mayor, Brooklyn, NY, Everyman Theatre, 3 November 1977; My Cup Ranneth Over, Brooklyn, NY, Everyman Theatre, 3 November 1977 (Music for 1978 revival by Henry Krieger); Judas, Santa Maria, CA, Pacific Coast Conservatory of the Performing Arts, April 1978; T-Shirts, Minneapolis, MN, Out-and-About Theatre, 19 October 1978; Mutual Benefit Life (full length), New York, Production Company, 27 October 1978; Bank Street Breakfast, New York, Fourth E, February 1979; The Family Bar, Hollywood, CA, Deja Vu, 1979; One Man, One Woman, New York, The Fourth at IATI, 16 February 1979; All in the Mind, New York, New York Theatre Ensemble, 1979; I’ll Tell It To You, Doctor Paroo, New York, New York Theatre Ensemble, 1979; The Sane Scientist, New York, New York Theatre Ensemble, 1979; Michelangelo’s Models (Music by Rob Feldstein), New York, New York Theatre Ensemble, 1981; 24 Inches (music by David Tice), New York, Theater for the New City, 1982; The Spinning Tree, Ohio Northern University, Ada, Ohio, 1982; Blue is for Boys, New York, Theater for the New City, 1983; music for 1986 revival by Tim Young and Robert Patrick; Nice Girl, New York, Theater for the New City, 1983; Beaux-Arts Ball, New York, Theater for the New City, 1983; The Comeback, New York, Theater for the New City, 1983; The Holy Hooker, Madison, WI, 1983; Loves of the Artists, Los Angeles, Deja Vu, 1983; 50’s 60’s 70’s 80’s, New York, Stonewall Repertory Theatre, 1983; Play-by-Play, New York, Douglas Fairbanks Studio, 1 March 1983; Big Sweet (music by LeRoy Dysart), Richmond Virginia, Richmond High, 1984; That Lovable Laughable Auntie Matter in “Disgustin’ Space Lizards,” New York, Cat Club, 1985; Bread Alone, New York, Wings Theatre, 1985; No Trojan Women (music by Catherine Stornetta), Waillingford, Connecticut, Choate, 1985; Left Out, Arroyo Grande, CA, Eagle Theatre, 1985; The Hostages, New York, 1985; The Trial of Socrates, New York, Wings Theatre, 1986; Bill Batchelor Road, Minneapolis, MN, 1986; On Stage, Ralston, NE, 1986; Why are They Like That?, Spokane, WA, 1986; Desert Waste, New York, Corner Loft, 1986; La Balance, New York, Theater for the New City, 1987; The Last Stroke, Edinburgh, Scotland, 1987; Explanation of a Christmas Wedding, New York, Theater for the New City, 1987; The Trojan Women, New York, Theater for the New City, 1987; Pouf Positive, New York, Dramatic Risks, 1987; Untold Decades (Music for final version by Patrick R. Brown), New York, Producers Club, 1988; Hello, Bob, New York, La Mama E.T.C., 11 October 1990; Ruminations, New York, Courtyard Playhouse, 1991; Harbor, New York, Courtyard Playhouse, 1992; Raise the Children, New York, Courtyard Playhouse, 1992; Sugar Cookies, Merced , CA, Merced High School, 1993; Interruptions, Merced, CA, Merced High School, 1993; Meet Marvin, New York, Courtyard Place, April 1993 (composed of a new monologue and two older one acts: Evan on Earth, which had never before been produced, and T-Shirts); November Dodo, Orlando, Florida, Theatre Dodo, July 1993; Hollywood at Sunset, New York City, TOSOS II, 2004.

OTHER: T-Shirts in Gay Plays: The First Collection, ed. William M. Hoffman (1979), 1-46; Simultaneous Transmissions in The Scene 2: Plays from Off Off Broadway, ed. Stanley Nelson (1974). “Kit” in Flesh and the Word #2, ed. John Preston (1993), 179-189; “After Hours at the Buono” in Flesh and the Word #3, ed.. Michael Lowenthal (1994), 75-81; “The War Over Jane Fonda” in The Mammoth Book of Gay Short Stories, ed. Peter Burton, (1997), 281-292; also in Contra/diction, ed. Brett Josef Grubisic (1998), 101-109 and “Tokyo Today,” (March 1992), 64-67; “Mass Ass” in Best Gay Erotica 2009, ed.Richard Labonte and James Lear (2008); “A Beautiful Face” in Best Gay Erotica 2010, ed. Richard Labonte and Blair Mastbaum (2009).

SELECTED PERIODICAL PUBLICATIONS–UNCOLLECTED: “Thank Heaven for Little Girls: An Examination of the Male Chauvinist Musical,” Cineaste VI, 1 (1973); 22-25, “Oh Purge Us, Dramaturge of Those Plays So Oft Regurged,” Dramatics 49.4 (March-April 1978): 15-19; Let Me Tell It to You (Dr. Paroo), Dramatics 49.4 (March-April 1978): 27-30; Starwalk, Dramatika, 7.12, Nos. 1 & 2 (Double Number); Un Bel Di, Performance No. 11, Ed, Erika Munk; See Other Side and Action, yale theatre magazine (dates of publication not available); “Gay Analysis,” TDR 22.3 (September 1978): 67-72; Judas in West Coast Plays 5 (Fall 1979): 1-90; “The Other Brick Road,” Other Stages (February 8-21, 1979), 3 and 10; “Will Power,” Curtain (1980) (publication information not available); Big Sweet: Act I, Dramatics 55.2 (October 1983): 29-39; Big Sweet: Act II, Dramatics 55.3 (November 1983): 13-19; “Gay Theater’s Relationship With Its Audience,” Christopher Street (December 23, 1991), 16-20; “The Four Wilsons: Understanding Gay Playwrighting,” Christopher Street (1992), 15-21; “The Student-Teacher Relationship,” The Thirteenth Moon (August 1993), 13-20; “Nudity on Stage in Greenwich Village,” Nude & Natural (1994), 46-47; “Caffe Cino: Memories by Those Who Worked There,” Los Angeles Theatre Magazine (November 1994), 1-5; reviews of gay male adult movies, AVN Magazine (2003-2009).

PUBLICATIONS ONLINE: See list HERE.

VIDEO ONLINE: Pioneers of Gay Theatre from the Caffe Cino.

RECORDING: Pouf Positive on CD Harvey Fierstein, This Is Not Going to Be Pretty, Plump Records (1999).

PAPERS: Robert Patrick’s papers are archived in La Mama E.T.C.’s Archives and the Billy Rose Theatre Collection of the New York Public Library.

MOVIES: Patrick appears in “Resident Alien,” “O Boys Parties, Porn and Politics,” and “Wrangler: Anatomy of an Icon“. ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

*Plays with homoerotic elements were also presented by Ronald Tavel, Peter Hartman, Jeffrey Weiss, George Birmisa, Jean-Claude van Itallie, Ruth Landschoff Yorck, Andy Milligan, and Allan Lysander James.

- Comment

- Reblog

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

February 23, 2010 at 6:50 am |

[…] WEBPAGE: http://robertpatrick.wordpress.com/ ROBERT PATRICK by Wendell Stone: https://pointlessplea.wordpress.com/2010/02/22/robert-patrick-by-wendell-stone/ POEMS: http://robertpatrick.wordpress.com/2009/05/28/a-strain-of-laughter/ GHOSTWRITNG […]

September 8, 2011 at 1:11 pm |

[…] https://pointlessplea.wordpress.com/2010/02/22/robert-patrick-by-wendell-stone/ […]